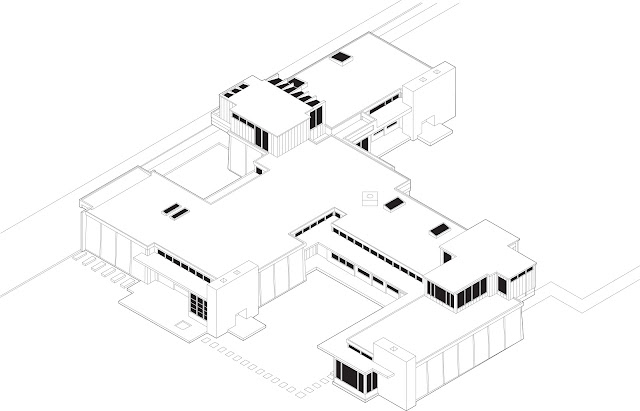

Schindler had a fascinating approach to early modern architecture,

he was ahead of his time. His ideals were different and thus, his house was too.

|

| Light play through window |

The Schindler-Chace house was revolutionary because it experimented with the absence of a central

heating system. (Hines, 244) While 1920's technology allowed for a comfortable mechanized indoor

climate, the Schindlers opted for fireplaces. (Hines, 244) The Schindlers and Chaces adapted to a lifestyle that conditioned

them to minimize the bodily discomforts of the cool Los Angeles evenings, not

only in the exposed rooftop sleeping baskets, but also in the unheated studios

after the fires died.(Hines, 244) The camping lifestyle became more than just a temporary

approach to life in Yosemite. It became a lifestyle choice that grew inside

Schindler himself, and as any house should be, it became a reflection of life.

What makes 835 North Kings Road unique is Schindler's

bohemian design. A graceful aura is captured by the structure, from the way

insulite panels are "few, thin and removable," to the adaptive

furniture. (Smith, Darling, 124) The house's studios adapt to its users requests. Unlike other homes

of the era, many rooms had no default program. The studios are left bare so

that a novelist, artist, draftsmen or anyone else could find them accommodating

for a creative lifestyle. (Smith, 21) The user is free to turn the space into whatever they

want. It's utterly breathtaking that the simplicity of these rooms is so

hospitable. Today we adapt rooms for certain needs, add vents, shelves and

other built-ins to push a program, to promote a certain type of work, but all

we need is the bare essentials. Schindler understood that. He simply made space, and let one breath in it.

|

| Bathroom with concrete bath and counter |

The simplicity of the house is hauntingly beautiful. It's meant to embody the idea of mans original home: the cave. (Smith, Darling, 124) The repeated slit

window openings, clerestories and redwood framed window walls allow light to

dance from the outside into the interior. The bathroom even has one of these

slits, allowing light to illuminate the

sink. (Smith, 57) Schindler used poured concrete to match the wall to form the bathtub and

vanity, completely unadorned.(Smith, Darling, 124) He opposed the idea of lavish porcelain fixtures. (Smith, Darling, 124) What he wanted to achieve was an

indigenous, cave-like feel. Even the fireplaces were left minimal. Instead of a

large hearth separated from the ground, Schindler's fireplace sits right on grade,

allowing the flames to rise right from the floor. (Smith, Darling, 124) These are just a few of the

details that display Schindler's ideas of a modern home, "a timid retreat."

The Schindlers stated that the house was intended to free

them of a traditional work day, yet the

house nonetheless required a lot of maintenance. (Smith,

21) The work required had to do

with the way the house was built. The wooden surfaces were untreated, and the

thin slits of glass fixed between concrete were always victim to cracking. (Hines,

244) To the Schindlers, the idea of a house was

grounded in the belief of constructing in a minimal or no refinement approach,

or as Pauline Schindler liked to put it, "the essences." (Hines,

244) The essences

avoided the practicalities of proper detailing. (Hines,

244) As a result, the house was

always under threat from the elements.

The 1922 house was otherworldly for the time, it didn't

conform to social expectations of a home. The Schindler Chace House uses a simple material palette and it promotes a simple life through lack of luxury. Yet at the same time, the inhabitants live lavishly knowing that they've got a completely original home.

+(1).jpg)